The following is an article from the book Uncle John's Bathroom Reader Plunges Into History Again.

The following is an article from the book Uncle John's Bathroom Reader Plunges Into History Again.

Dance marathons started out as innocent fun but wound up as grim as the Depression that ended them.

Post-World War I America was in a mood to break all records: popular events included endurance kissing and hand-holding contests, eating marathons, and flagpole sitting. A guy named Shipwreck Kelly became national celebrity after sitting atop a flagpole for 7 days, 13 hours, and 13 minutes. When someone challenged Bill Williams to push a peanut up Pike's Peak with his nose, he agreed. It took him 30 days, and he won $500 (415 euros) for the feat. It all had to do with the mood of the day. But nothing caught the public's fancy as much as dance marathons.

A CRAZE IS BORN

The birth of U.S. dance marathons can be traced to early 1923 when, inspired by a record set in Britain a few weeks earlier, Miss Alma Cummings took to the floor of the first American dance marathon, which was held in New York City's somewhat seedy Audobon Ballroom. Cummings wore out six males partners over the next 27 hours and won a world record. Within a week, a French college student broke that record. A few days later, Cummings retook the title, which was soon broken again, this time by a Cleveland, Ohio, salesgirl. The challenge was on.

A few weeks after Cummings' win, a Texas dance hall owner got the brilliant idea of charging spectators admission (25¢ during the day, $1 at night). He gave his first winner -Miss Magdalene Williams- a prize of $50 (42 euros). On April 16, Cleveland's Madeline Gottschick beat William's record with a time of 66 hours. Within days, that record was broken three times. On June 10, Bernie Brand danced for 217 hours (more than 9 days) and went home with $5,000 (4,151 euros) in prizes. In just a few months in 1923, the dance marathon had swept the nation and the world. And so it continued throughout the 1920s.

THE DOWNBEAT

The deaths of a few supposedly healthy young people -including 27-year-old Homer Morehouse from heart failure after 87 hours of dancing- brought some unwelcome attention. Officials banded together with church groups (who saw the marathons as immoral) and movie theater owners (who saw the marathons as competition) to try to stomp out the fad. Critics called the contestants "dangerous, useless, and disgraceful," and they even likened them to the dancing manias of 14th-century Europe.

TAKE A LOAD OFF

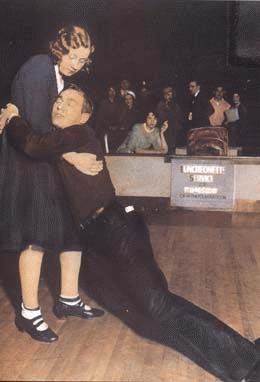

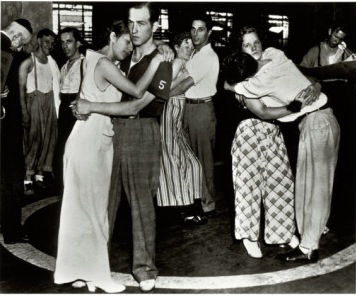

In an effort to save their golden goose, promoters added rest periods during which the dancers could lie down on cots, take hot showers, or have their injuries seen to. Some even let dancers take a short walk outside, but eating was still done while dancing, at chest-high buffet tables set up mid-floor. The length and spacing of rest periods varied from contest to contest: 15 minutes every hour, 11 minutes out of every 90 minutes, and so on. Another change was that couples versus individual contestants became the norm. But a dancer wasn't stuck with one partner for the duration. If your partner gave out, you could dance solo for a set amount of time while seeking another, healthier partner in the group. Now, thanks to rest periods and partners who could hold you up while you slept, a marathon could last for weeks. But watching a dance floor full of droopy couples wasn't going to hold the crowd's attention, so vaudeville skits were added. So were professional dancers, who worked the crowd and posed as good guys and bad guys, like modern day pro wrestlers.

A marathon that started with 100 contestants would dwindle to the hard core after a week or two. The remaining couple would drag themselves across the floor, but at specific times the emcee would make an announcement, and the dancers would be expected to run a ten-minute footrace or perform an all-out foxtrot or tango -the losers of which would be eliminated.

TALK ABOUT DEPRESSING

Marathons were well established by the arrival of the Depression in 1929, and they became the perfect escape. If you could scrape together the admission, you could come in out of the weather and be entertained; if you were young and strong enough, you could enter and try to win a few thousand dollars. Even if you lost, you'd be well taken care of while you lasted: three square meals, snacks, and medical teams to treat your injuries and give you rubdowns. Of course, you could be mistreated, too, by "grinds," show employees whose job it was to prod contestants who fell behind, or generally harass the dancers to keep things exciting. Promoters staged weddings and fights and it was hard to differentiate between what was staged or genuine. But there was plenty of real drama: sleep-deprived dancers suffered hallucinations and delusions, hysteria, and bouts of temporary amnesia.

THE DANCE IS ENDED

By the mid-1930s, the contests had lost their glitter. What had been lighthearted entertainment became a struggle for survival, and it showed. Dance marathons weren't fun anymore. The country was in a Depression in more ways than one. The marathoners, once viewed a respectable and plucky, were now viewed as being no better than the vagrants who traveled the country looking for food or work. They became a reminder of the failed American dream; a symbol of just how low the country had fallen. One by one, states and cities across the country banned dance marathons. The shows continued on a small scale until the mid-1940s, but their heyday had long passed. Danceathons gave way to walkathons, which gave way to skateathons, which birthed the roller derby. But that's another story.

______________________________

The article above is reprinted with permission from Uncle John's Bathroom Reader Plunges Into History Again. The book is a compendium of entertaining information chock-full of facts on a plethora of history topics. Uncle John's first plunge into history was a smash hit - over half a million copies sold! And this sequel gives you more colorful characters, cultural milestones, historical hindsight, groundbreaking events, and scintillating sagas.

The article above is reprinted with permission from Uncle John's Bathroom Reader Plunges Into History Again. The book is a compendium of entertaining information chock-full of facts on a plethora of history topics. Uncle John's first plunge into history was a smash hit - over half a million copies sold! And this sequel gives you more colorful characters, cultural milestones, historical hindsight, groundbreaking events, and scintillating sagas.

Since 1988, the Bathroom Reader Institute had published a series of popular books containing irresistible bits of trivia and obscure yet fascinating facts. Check out their website here: Bathroom Reader Institute