The following is an article from Uncle John's Curiously Compelling Bathroom Reader.

Here's a little-known slice of Americana: the story of how freed slaves changed the face of the American West.

LAND OF OPPORTUNITY

In 1865 the American Civil War came to an end and four million black slaves were free. But to what future? The South lay in ruins, its plantation economy shattered. Most slaves had been field workers or tenant farmers, and working the land was the only job they knew. Although they were now free to buy land to farm, few had the money. Even worse, a new terror was rising across the South as hostile white, bitter in defeat, donned the white hoods of the Ku Klux Klan and began to terrorize the black community. But there was a way out ...and it lay to the west.

The Homestead Act of 1862 offered grants of 160 acres of public lands on the Great Plains to anyone who would farm the land for five years. Thousands of Southern blacks joined the flood of settlers heading west to what they called "Beulah Land" -the Promised Land- only their mission was slightly different. Yes, the promise of owning their own land was sweet. But sweeter still was the possibility of living independent lives untouched by fear and racism. So they banded together and developed all-black communities, with their own banks, their own newspapers, their own businesses, and their own schools and colleges.

OKLAHOMA, THE ALL-BLACK STATE?

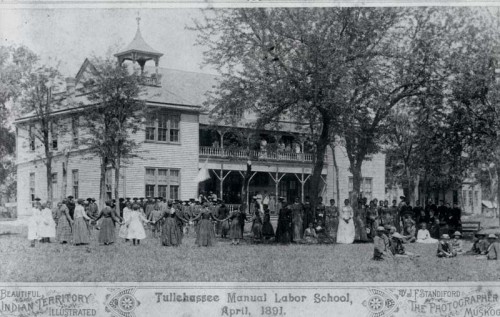

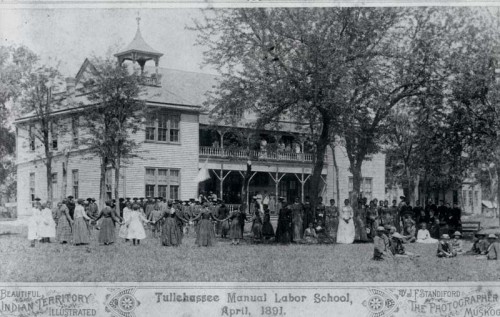

Although blacks migrated to every state and territory in the West, the territory of Oklahoma became the preferred place to settle: A sizable number of African-Americans already lived there, having come as slaves with the Cherokee and other tribes during the Trail of Tears in 1838. After emancipation they bought land in Indian territory (often with the help of the Indians, who, under fierce pressure to give up their land to new settlers, preferred to sell it to black Americans). A number of black leaders, such as Edward P. McCabe and Hannibal C. Carter, led the push.

Carter established the Freedmen's Oklahoma Immigration Association in Chicago in 1881 specifically to help blacks move to Oklahoma. They even convinced one U.S. Senator -Henry W. Blair of New Hampshire- to introduce a bill to make Oklahoma an all-black state. That legislation never passed, but the Land Run of 1889 opened up even more Oklahoma land to black settlers, leading to the establishment of scores of black towns. Using 360 acres won in the Land Run, McCabe founded the town of Langston, named after John H. Langston, a black congressman from Virginia. Dubbing it "The Only Distinctive Negro City in America," McCabe used his newspaper, the Langston City Herald, to promote the town to black communities back in the South. Langston University, founded in 1908, is the only remaining historically black college in Oklahoma.

BROUGHT LOW BY JIM CROW

By 1910 there were 59 all-black towns across the west, 29 in Oklahoma alone. Their successes were hard won: As more and more whites came into the area, they brought with them the racist attitudes that prevailed in the rest of the country. The early 20th century was the era of "Jim Crow," as the discriminatory laws and practices designed specifically to limit and suppress the rights of black people were not only acceptable, but were the order of the day. (The name Jim Crow dates back to the minstrel shows of the 1830s, where white performer Jim "Daddy" Rice blackened his face with burnt cork and danced a jog while singing the lyrics to a song called "Jump Jim Crow." His parody of a dancing black man became so well known that by the Civil War, the words "Jim Crow" had become a racial slur.)

In Oklahoma, the white majority-controlled legislature began passing laws blocking black immigration into the state and limiting where blacks could buy land. Black businesses and farmers were allowed to buy and sell their services and their crops only within their own small communities. Worse yet, they could only borrow from black-owned banks, which made them vulnerable to even the slightest downturn in the economy. But the death knell of the black townships in Oklahoma sounded in 1921 in Greenwood, an all-black district of Tulsa.

THE GREENWOOD RIOTS

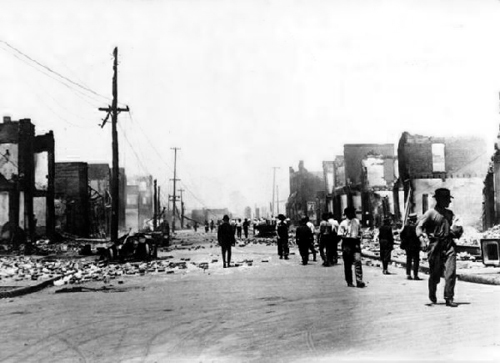

In 1921 the town of Greenwood, Oklahoma -dubbed "The Black Wall Street"- was one of the most prosperous black communities in America. More than 190 businesses were licensed to operate in the community of 11,000 residents. (Tulsa at the time had 70,000.) There were fifteen doctors, three lawyers, two dentists, and a chiropractor, as well as two schools, two theaters, several hotels, a library, and a hospital. Greenwood was a model of black enterprise and self-sufficiency.

It all changed on May 31, 1921. There are varying accounts of how it all began, but like so many acts of race-related violence in the United States, it involved a white woman and a black man. Something happened in a building in downtown Tulsa between a 17-year-old elevator operator named Sarah page and 19-year-old Dick Rowland. The most commonly accepted version of the story is that Rowland stepped on the girl's foot. When she started to fall, he tried to catch her. She screamed, and he ran away. Word quickly spread through the white community that Rowland had "assaulted" the girl. When a local paper ran an inflammatory headline encouraging local whites to "nab the negro," events spiraled out of control.

CHAOS AND DISASTER

Whites gathered outside the courthouse where Rowland was being held, demanding that he be turned over to the mob. Meanwhile, worried blacks came together in Greenwood, determined to stop the lynching. The crowd at the courthouse swelled to 2,000. About 75 blacks went to the courthouse, and in the confrontation that followed, a shot was fired. Within seconds the street erupted in a gunfight. The outnumbered blacks retreated to Greenwood, pursued by a rampaging mob that looted and burned stores and homes along the way.

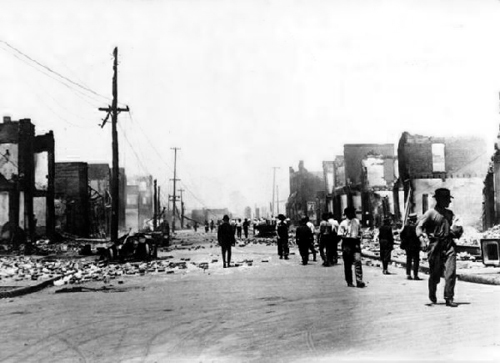

Violence raged for the next 16 hours. Bands of whites drove through the streets of Greenwood, shooting any black person they saw. One black man tried to escape by running into a theater; the mob caught and murdered him on the stage. Many blacks fled the city. Those who stayed behind were rounded up and placed in internment camps. When the National Guard finally restored order, Greenwood was in ruins. At least 150 people were dead and 1,200 homes and businesses were burned to the ground. Aside from the loss of life, property damage was estimated at $1.5 million. The black community never recovered from the disaster. No arrests were ever made, and some months later the case against Dick Rowland was dismissed when Sarah Page chose not to press charges.

SURVIVORS

The financial crash of 1929, followed by the hard times of the Great Depression and agricultural losses of the Dust Bowl, brought an end to those early glory days of black self-sufficiency in the Midwest. Many black township residents fled west to California or north to Chicago, looking for work or a better way of life.

Today only 13 of the 29 predominantly black towns in Oklahoma still exist: Boley, Brooksville, Clearview, Grayson, Langston, Lima, Redbird, Rentiesville, Summit, Taft, Tatums, Tullahassee, and Vernon. They remain a living testimonial to the courage and grit of the former slaves who founded them, and the American Dream they hoped to find out West.

The article above is reprinted with permission from Uncle John's Curiously Compelling Bathroom Reader, a fantastic book by the Bathroom Readers' Institute.

The article above is reprinted with permission from Uncle John's Curiously Compelling Bathroom Reader, a fantastic book by the Bathroom Readers' Institute.

The 19th book in this fan-favorite series contain such gems like The Greatest Plane that Never Was, Forgotten Robot Milestones, Ancient Beauty Secrets, and more.

Since 1988, the Bathroom Reader Institute had published a series of popular books containing irresistible bits of trivia and obscure yet fascinating facts.

If you like Neatorama, you'll love the Bathroom Reader Institute's books - go ahead and check 'em out!

Here's a little-known slice of Americana: the story of how freed slaves changed the face of the American West.

LAND OF OPPORTUNITY

In 1865 the American Civil War came to an end and four million black slaves were free. But to what future? The South lay in ruins, its plantation economy shattered. Most slaves had been field workers or tenant farmers, and working the land was the only job they knew. Although they were now free to buy land to farm, few had the money. Even worse, a new terror was rising across the South as hostile white, bitter in defeat, donned the white hoods of the Ku Klux Klan and began to terrorize the black community. But there was a way out ...and it lay to the west.

The Homestead Act of 1862 offered grants of 160 acres of public lands on the Great Plains to anyone who would farm the land for five years. Thousands of Southern blacks joined the flood of settlers heading west to what they called "Beulah Land" -the Promised Land- only their mission was slightly different. Yes, the promise of owning their own land was sweet. But sweeter still was the possibility of living independent lives untouched by fear and racism. So they banded together and developed all-black communities, with their own banks, their own newspapers, their own businesses, and their own schools and colleges.

OKLAHOMA, THE ALL-BLACK STATE?

Although blacks migrated to every state and territory in the West, the territory of Oklahoma became the preferred place to settle: A sizable number of African-Americans already lived there, having come as slaves with the Cherokee and other tribes during the Trail of Tears in 1838. After emancipation they bought land in Indian territory (often with the help of the Indians, who, under fierce pressure to give up their land to new settlers, preferred to sell it to black Americans). A number of black leaders, such as Edward P. McCabe and Hannibal C. Carter, led the push.

Carter established the Freedmen's Oklahoma Immigration Association in Chicago in 1881 specifically to help blacks move to Oklahoma. They even convinced one U.S. Senator -Henry W. Blair of New Hampshire- to introduce a bill to make Oklahoma an all-black state. That legislation never passed, but the Land Run of 1889 opened up even more Oklahoma land to black settlers, leading to the establishment of scores of black towns. Using 360 acres won in the Land Run, McCabe founded the town of Langston, named after John H. Langston, a black congressman from Virginia. Dubbing it "The Only Distinctive Negro City in America," McCabe used his newspaper, the Langston City Herald, to promote the town to black communities back in the South. Langston University, founded in 1908, is the only remaining historically black college in Oklahoma.

BROUGHT LOW BY JIM CROW

By 1910 there were 59 all-black towns across the west, 29 in Oklahoma alone. Their successes were hard won: As more and more whites came into the area, they brought with them the racist attitudes that prevailed in the rest of the country. The early 20th century was the era of "Jim Crow," as the discriminatory laws and practices designed specifically to limit and suppress the rights of black people were not only acceptable, but were the order of the day. (The name Jim Crow dates back to the minstrel shows of the 1830s, where white performer Jim "Daddy" Rice blackened his face with burnt cork and danced a jog while singing the lyrics to a song called "Jump Jim Crow." His parody of a dancing black man became so well known that by the Civil War, the words "Jim Crow" had become a racial slur.)

In Oklahoma, the white majority-controlled legislature began passing laws blocking black immigration into the state and limiting where blacks could buy land. Black businesses and farmers were allowed to buy and sell their services and their crops only within their own small communities. Worse yet, they could only borrow from black-owned banks, which made them vulnerable to even the slightest downturn in the economy. But the death knell of the black townships in Oklahoma sounded in 1921 in Greenwood, an all-black district of Tulsa.

THE GREENWOOD RIOTS

In 1921 the town of Greenwood, Oklahoma -dubbed "The Black Wall Street"- was one of the most prosperous black communities in America. More than 190 businesses were licensed to operate in the community of 11,000 residents. (Tulsa at the time had 70,000.) There were fifteen doctors, three lawyers, two dentists, and a chiropractor, as well as two schools, two theaters, several hotels, a library, and a hospital. Greenwood was a model of black enterprise and self-sufficiency.

It all changed on May 31, 1921. There are varying accounts of how it all began, but like so many acts of race-related violence in the United States, it involved a white woman and a black man. Something happened in a building in downtown Tulsa between a 17-year-old elevator operator named Sarah page and 19-year-old Dick Rowland. The most commonly accepted version of the story is that Rowland stepped on the girl's foot. When she started to fall, he tried to catch her. She screamed, and he ran away. Word quickly spread through the white community that Rowland had "assaulted" the girl. When a local paper ran an inflammatory headline encouraging local whites to "nab the negro," events spiraled out of control.

CHAOS AND DISASTER

Whites gathered outside the courthouse where Rowland was being held, demanding that he be turned over to the mob. Meanwhile, worried blacks came together in Greenwood, determined to stop the lynching. The crowd at the courthouse swelled to 2,000. About 75 blacks went to the courthouse, and in the confrontation that followed, a shot was fired. Within seconds the street erupted in a gunfight. The outnumbered blacks retreated to Greenwood, pursued by a rampaging mob that looted and burned stores and homes along the way.

Violence raged for the next 16 hours. Bands of whites drove through the streets of Greenwood, shooting any black person they saw. One black man tried to escape by running into a theater; the mob caught and murdered him on the stage. Many blacks fled the city. Those who stayed behind were rounded up and placed in internment camps. When the National Guard finally restored order, Greenwood was in ruins. At least 150 people were dead and 1,200 homes and businesses were burned to the ground. Aside from the loss of life, property damage was estimated at $1.5 million. The black community never recovered from the disaster. No arrests were ever made, and some months later the case against Dick Rowland was dismissed when Sarah Page chose not to press charges.

SURVIVORS

The financial crash of 1929, followed by the hard times of the Great Depression and agricultural losses of the Dust Bowl, brought an end to those early glory days of black self-sufficiency in the Midwest. Many black township residents fled west to California or north to Chicago, looking for work or a better way of life.

Today only 13 of the 29 predominantly black towns in Oklahoma still exist: Boley, Brooksville, Clearview, Grayson, Langston, Lima, Redbird, Rentiesville, Summit, Taft, Tatums, Tullahassee, and Vernon. They remain a living testimonial to the courage and grit of the former slaves who founded them, and the American Dream they hoped to find out West.

____________________________________

The article above is reprinted with permission from Uncle John's Curiously Compelling Bathroom Reader, a fantastic book by the Bathroom Readers' Institute.

The article above is reprinted with permission from Uncle John's Curiously Compelling Bathroom Reader, a fantastic book by the Bathroom Readers' Institute.The 19th book in this fan-favorite series contain such gems like The Greatest Plane that Never Was, Forgotten Robot Milestones, Ancient Beauty Secrets, and more.

Since 1988, the Bathroom Reader Institute had published a series of popular books containing irresistible bits of trivia and obscure yet fascinating facts.

If you like Neatorama, you'll love the Bathroom Reader Institute's books - go ahead and check 'em out!

That makes no sense whatsoever. You may want to visit a dictionary.

On a side note, They said at the height of financial success in Greenwood, you could bring a dollar into the local economy and it would change hands for 3 weeks before leaving. Greenwood could have been something.