Chicago grew up fast. In 1840, it was a quiet settlement of 4,500 people. Three decades later, it had grown to a vibrant metropolis of 300,000. Unfortunately, the city planners didn't take much stock of the materials they were using. From the planks of the sidewalks to the shingles on the roofs, the new city was built almost entirely of wood. And in the autumn of 1871, all of that came to a head.

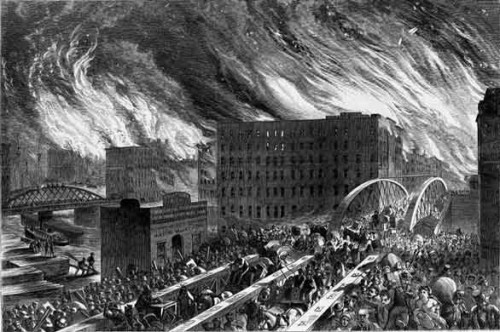

On October 8, during a particularly dry and windy spell, the wood and weather combined to make combustion history. That night, the Great Chicago Fire broke out in a DeKoven Street barn. (The O'Leary family owned it, but their cow had nothing to do with the fire.) The flames advanced quickly, engulfing nearby lumberyards and the city's downtown, and they burned for 36 hours straight. In the end, 18,000 structures were destroyed, as many as 300 people were killed, and nearly one-third of the population was left homeless.

Yet, the enduring legacy of the Great Chicago Fire is not its destruction, but the amazing rebirth that took place after it.

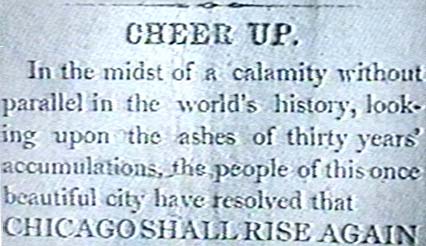

The rebuilding of Chicago began with Joseph Medill, managing editor and publisher of the Chicago Tribune, who personified the city's indomitable spirit. Even though the blaze had partially leveled his newspaper's headquarters, Medill cranked out a special edition two days later, affirming the city's resolve with an editorial stating, "Cheer up ... Chicago Shall Rise Again." It was more than empty encouragement. One month later, Medill was elected mayor on the city's "Fireproof" ticket. He immediately ushered in safety reforms that set the stage for rapid development and a new wave of construction.

Within 10 years, the population of Chicago had nearly doubled. Soon, there was no more land to build on, and overcrowding was setting in. But in 1883, architect William Le Baron Jenney came up with a novel solution. He designed the innovative, 10-story Home Insurance Building -widely considered to be the world's first skyscraper. The Home Insurance Building had the steadiness of a cathedral, but at a third of the normal weight. Jenney's genius was in using a light steel frame covered in hollow terra cotta tiles to prevent the spread of fire. His skyscraper inspired architects to think vertically and gave rise not just to Chicago's skyline, but also to new skylines across the globe.

CITY MEETS WORLD

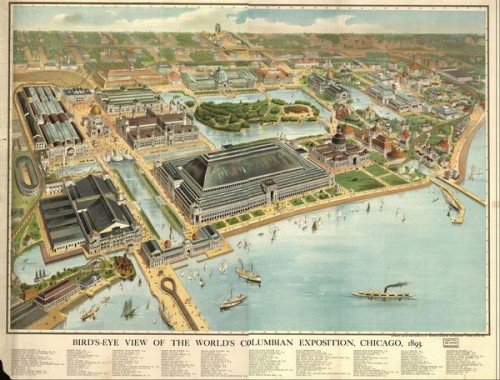

By 1890, less than two decades after the Great Fire, more than 1 million people were living in Chicago. It surpassed Philadelphia in population, and became America's "second city", next only to New York. Despite its size, many saw Chicago as a glorified hick town. To change that perception, Chicago competed with New York to host the world's Columbian Exposition, a fair to commemorate the 400th anniversary of Columbus' arrival in America. At the time, World's Fairs were serious business. They had the power to thrust a host city into the global spotlight and bring in enormous revenue and prestige.

While New York had financial titans like J.P. Morgan and William Waldorf Astor bidding in its corner, Chicago had something more compelling -a collective sense of purpose. Department store mogul Marshall Field, who'd lost his original building in the blaze, and industrialist Cyrus McCormick, who'd also lost his factory, pledged a combined $15 million to underwrite the fair. Then an even more surprising thing happened: The taxpayers voted for a referendum pledging an additional $5 million. To them, the World's Fair wasn't just a celebration; it was a chance at rebirth.

In the end, Congress decided that Chicago's bid was stronger than New York's, and the city went on to host one of the most successful World's Fairs in history. The 1893 event introduced the world to ragtime music, shredded wheat, hamburgers, postcards, neon lights, and the Ferris wheel. It also influenced architecture for decades to come. The fairground's classical buildings inspired the nationwide City Beautiful movement, which led to the creation of the National Mall in Washington, DC, and the fair's layout inspired modern amusement parks, such as Disneyland. The buildings even sparked the imagination of writer L. Frank Baum, who created the Emerald City in their image in his book The Wonderful Wizard of Oz.

On October 9, 1893, on the 22th anniversary of the Great Fire, 716,881 people visited the World's Fair in one day, shattering all previous Fair attendance records. In just 22 years, Chicago had risen from a pile of rubble to the height of civilization -and the world was there to celebrate.

__________________________

The article by Christopher Zara is reprinted from the May- June 2010 issue of mental_floss magazine. You can order back issues of mental_floss or get a subscription to have each issue delivered to you!

The article by Christopher Zara is reprinted from the May- June 2010 issue of mental_floss magazine. You can order back issues of mental_floss or get a subscription to have each issue delivered to you!Be sure to visit mental_floss' website and blog for more fun stuff!

Atlanta is already associated with the Phoenix due to it's burning during the Civil War.

It even uses the Phoenix in it's city seal.

1,875 square miles burned, 1,200+ dead.